Drax Hall and Dorset

Dr Paul Lashmar discusses the Drax family, slavery, poor treatment of farm workers, and how local Unite members helped his research.

Reading time: 6 min

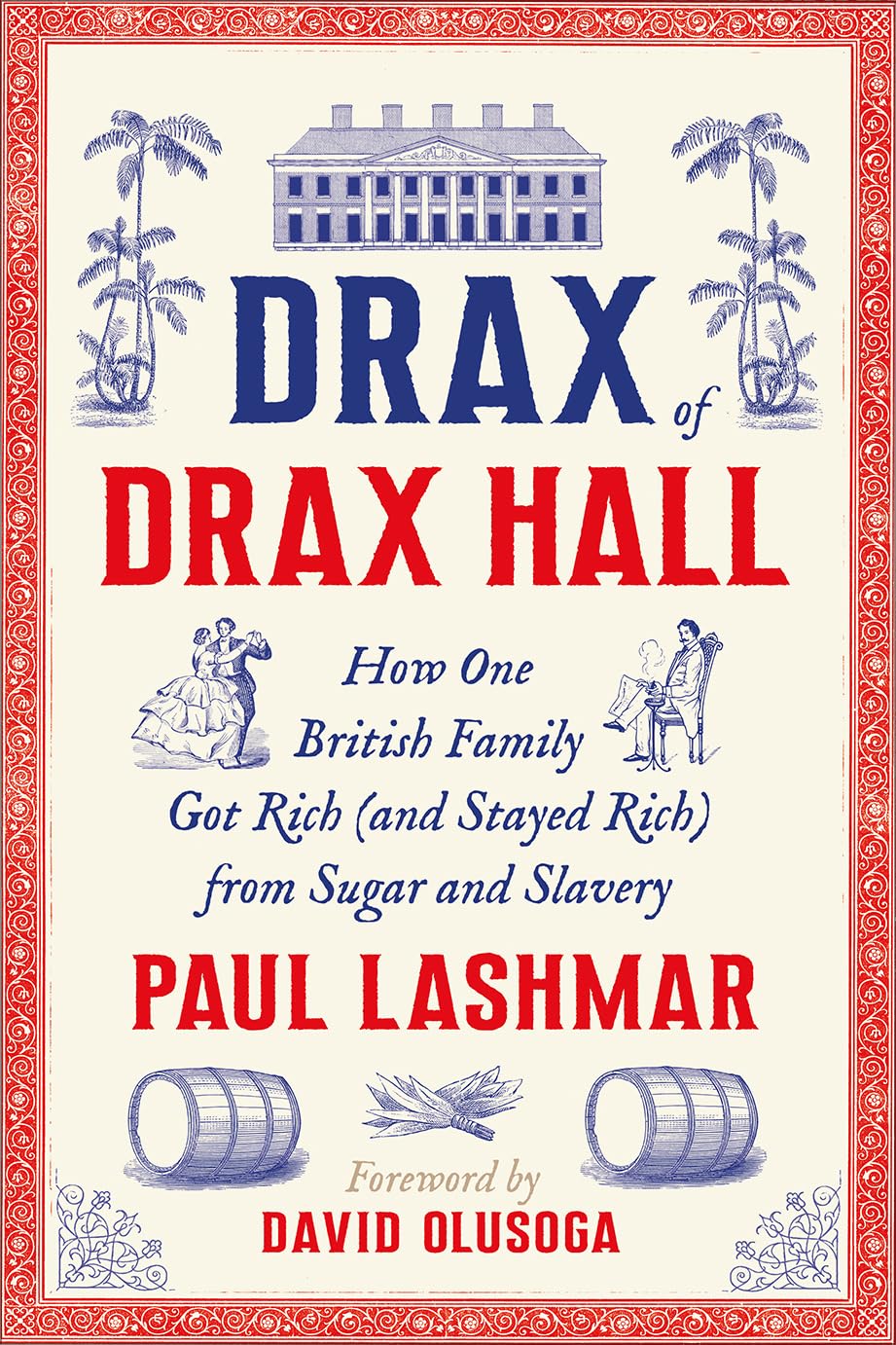

In my book Drax of Drax Hall: How One British Family Got Rich (and Stayed Rich) from Sugar and Slavery, I make the point that the Plunkett Ernel-Erle-Drax family are unique in still having an unbroken history of owning sugar plantations in the Caribbean from their inception in the early 17th century until the present day. In other ways though, they are typical of the landed gentry families that made vast sums from using enslaved people from Africa to work their plantations in the colonies. Many of these families also had large estates back in Britain.

I draw on the Plunkett Ernle-Erle-Drax family as a case study to look at the way these families treated their workforces in both the colonies and back at home. I am grateful to the members of Unite who have helped me tell this story. John Burridge, the Dorset Unites farmworkers rep helped me understand modern farming practices, Grafton Straker who has hid roots in Barbados and is a Unite rep from Richard Drax’s old constituency in Purbeck. Grafton shared the books’ Dorset launch event platform with me giving a Barbados perspective. Keith Hatch from Bridport has been very supportive of the project. I was also privileged to give a talk about the book at the Tolpuddle Festival this year.

The Drax Hall plantation in St Georges Parish, Barbados was inherited from his father, who died in 2017, by his eldest son Richard Drax, who was the Conservative MP for South Dorset from 2010 to 2024, when Labour took his seat. Their ancestor James Drax (c.1609-1662) was one of the first settlers in Barbados in 1627 and is credited with inventing the British sugar industry in the 1630s. Around 1640 he developed the integrated sugar plantation. It was a highly efficient industrial process but required a coordinated workforce working from before sunrise to sunset. James Drax was the first planter in the British empire to move to a workforce to chattel slavery where even the children of slaves were held in perpetuity

Although he is a public figure, Richard Drax and his family are very private, not least about their wealth which is locked into a number of trusts. As head of the family, the former MP lives in the 17th-century grade 1 listed Charborough House with its 1,500 acres of parkland all tucked away behind the three miles of the “Great Wall of Dorset”. The Erle line of the family have owned the Charborough Estate since 1549.

Writing for The Observer and Sunday Mirror in 2020, I and my co-writer revealed Richard Drax and his family owned at least 15,000 acres of farmland, heathland and woodland in Dorset plus a farming estate and grouse moor in Yorkshire. We calculated that his 125-plus properties and 23.5 square miles of Dorset land are worth at least £150 million. We also revealed that he had personally inherited the Drax Hall plantation in Barbados, which was valued in 2020 as worth £4.7 million.

The conditions in which enslaved people in Barbados worked from the 1630s to the 1830s and were treated is truly horrific and they were often whipped and beaten and those who did not die on the voyage from Africa often had short tragic lives on the plantation.

While British agricultural workers did not suffer the horrific conditions of slavery, their lives could be very tough. Dorset agricultural workers were among the worst paid in England in the 19th century, and this fact was central to rural unrest in the county.

By the early–mid 19th century, weekly wages for farm labourers in Dorset were often as low as 7–9 shillings per week, compared with 10–12 shillings in many other southern counties and even higher in the Midlands and the North. This made Dorset the poorest counties for rural labourers. Agricultural workers in Dorset relied heavily on seasonal work and on parish relief (the Poor Law). Food prices, especially bread, could take up almost all of a labourer’s income, leaving families in near-starvation conditions.

It is little known that Charborough was one of the first targets of the Captain Swing protestors in Dorset in 1830. They marched on Charborough. The then owner John Sawbridge Erle Drax met the protestors on the way and agreed to have his tenant farmers pay the farmworkers 10 shillings an hour. When the protests subsided landowners gradually returned wages to their pre-1830 low.

In 1834 the Tolpuddle Martyrs (the six Dorset farm workers who formed a union and were transported to Australia) became symbols of how desperate conditions were for labourers in that area. Tolpuddle is just eight miles from Charborough.

Social reformers and government reports of the time (e.g., the Royal Commission on the Employment of Children, Young Persons, and Women in Agriculture, 1867) frequently highlighted Dorset as a county where rural wages and living conditions were at the bottom end of the national scale.

By the Second World War the Charborough Estate included some 30 farms which had once been family farms for the Stockleys, Ekins, Rokes and others who had to sell up during the agricultural downturns. Only their names remain as a reminder.

Today, the estate is farmed by contract and has at least 3000 acres growing cereals, oilseed rape and poppies and vast woodlands worked in conjunction with the Forestry Commission. In Barbados the (paid) workers cropped sugar there in the Spring, as has been done since the 1630s.

The social order remains much as it has for centuries.

Drax of Drax Hall: How One British Family Got Rich (and Stayed Rich) from Sugar and Slavery. An unauthorised history of the Drax family. Pluto Books (2025)