Extreme weather safety call

Unite delegates demand greater protections in extreme weather events

Reading time: 5 min

Unite delegates were queuing up to take part in a debate on extreme weather in the workplace, with contributors all having a personal story to share about their employer’s negligence in storms and heatwaves.

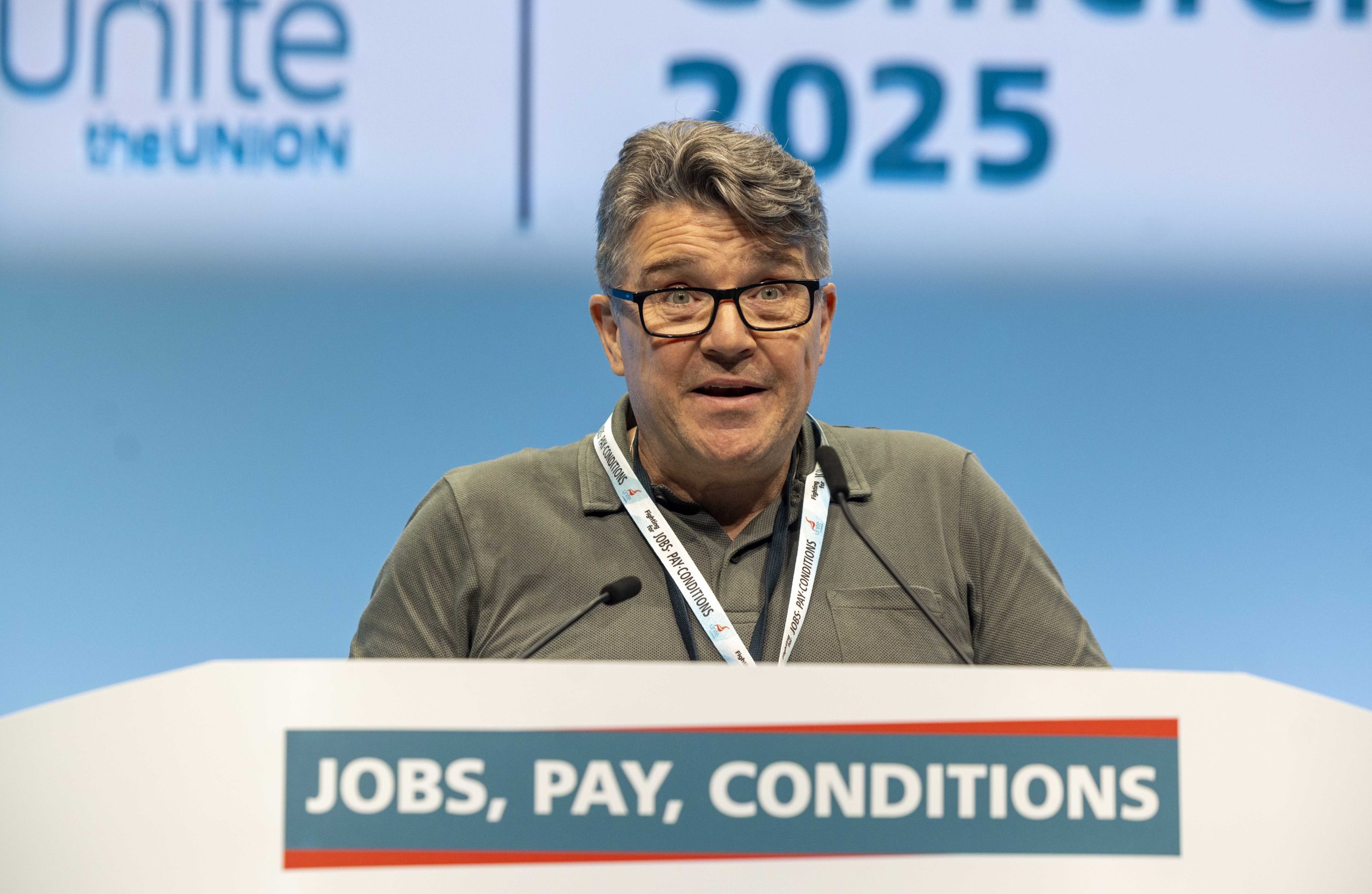

Moving the composite on Monday (July 7) was Unite delegate Justin Clarke of the Republic of Ireland (ROI). He explained how it is workers who are often literally and figuratively “caught in the eye of the storm” in extreme weather events, with employers failing to protect their workers.

He highlighted the untimely death of Unite member Matthew Campbell, an electrician who was forced to work during Storm Ali in 2018, and was killed by a fallen tree that had blown over in heavy wind gusts. His employer ignored an amber weather warning and failed to conduct a risk assessment.

Unite has taken the lead alongside Matthew’s family to fight for justice for Matthew, as they also call for a ‘Matthew’s Law’.

Justin went on to highlight a recent survey of Unite members of their experiences at work during Storm Éowyn earlier this year.

“The results of this survey exposed a cavalier approach of many employers to the safety of their employees,” he said, adding that he himself works for a “cavalier employer”.

Justin recounted how his employer totally ignored a red weather warning and demanded workers continue working, even when a roof had blown off in the storm.

“It was us, Unite reps, who had forced the closure of that business for three days,” Justin said to thunderous applause in the hall.

Unite is now working with politicians in both the ROI and Northern Ireland to identify how protections for workers can be improved. Justin highlighted some of the policy interventions that have worked in other countries, such as in Spain, where employees are given the right to four days’ paid climate leave for extreme weather.

Other Unite demands include protections for workers at and on their way to work, a maximum working temperature, and the requirement that employers close all non-essential workplaces under red or amber weather warnings.

Unite delegate Mark Dunne, of London & Eastern region, seconded the composite.

“We can no longer accept inadequate plans for climate change,” he said. “The evidence is clear – these extremes will continue, and they will worsen. We can no longer tolerate workplaces that are ill equipped to meet weather extremes, nor the expectation that workers just push through.”

Dunne spoke of the impact of recent heatwaves, where three London bus drivers were hospitalised with heat stroke. Temperatures in their cabs, he said, exceeded 40 degrees.

Unite delegate Lotte Fisher, who works in hospitality in Scotland, highlighted the harrowing experiences of hospitality workers, the majority of whom were asked to work during Storm Éowyn.

This, Lotte said, “was despite a red weather warning that constituted a major threat to life”.

“The venues that did shut only shut after enough workers refused to go in, or after public pressure. This made clear how willing these employers are to risk their employees’ safety in the pursuit of even minor financial gain.”

But Lotte added that after a single weekend during the storm, Unite recruited hundreds of hospitality workers in what she called a “uniquely politicizing event”.

Unite delegate Laszlo Marothy of the North West region also spoke in support of the motion. Laszlo works for an airline which he said has repeatedly risked workers’ safety.

Laszlo said that his employer’s response during Storm Éowyn left cabin crew and pilots terrified for their lives.

“[Staff] were told [by weather alerts] that they shouldn’t leave their homes because it is unsafe; their car insurance would be cancelled if they did. They were absolutely petrified, and all they got from their employer was transactional responses.”

Unite reps were left to communicate with workers who were “petrified” about leaving their homes during the storm.

Laszlo recounted how after they raised a grievance with their employer over their storm response, the employer argued over semantics, noting that they had told workers “to only go in if they felt safe” rather than “It is not safe – do not go into work.”

“We understand the difference; they do not,” Laszlo said. “All these workers asked for in our grievance was exactly what the motion calls for – weather-related risk assessments and alert-based responses. They said no to this.”

And so if employers won’t do it, they must be forced to, Laszlo continued.

“The responsibility of deciding whether it’s safe to leave your house and go to work should lie not with the workers, but with the employers,” he added.

The composite was overwhelmingly carried.

By Hajera Blagg

Photos by Mark Thomas